This is the second in a three-part series tracing Claude’s life in postwar New York and the early days of The Banyan Press—a time of artistic momentum, personal reckoning, and quiet transformation. These entries follow Claude and his partner Milton Saul as they begin to shape what the press might become. They also capture his deepening friendship with Anaïs Nin, and his immersion in a creative world filled with artists, writers, booksellers, and gallerists that stretched across the city and radiated outward.

Claude Fredericks (1923–2013) kept one of the longest personal journals ever written—more than 65,000 pages across eight decades, now housed at the Getty Research Institute. A printer, playwright, teacher, and diarist, Claude recorded everything: daily rhythms, private longings, and moments of profound artistic insight. Through his Banyan Press, he published works by Gertrude Stein, André Gide, James Merrill, and many others. Since January, I’ve been sharing excerpts from his journal here on Extracts—inviting readers into a life fully observed, and fully written.

New York City, April 1947

Claude is twenty-three, living in a cold-water flat off Third Avenue with his partner, Milton Saul. The El shudders past their windows. They’re setting type, testing paper stocks, baking bread, writing poems, making love—and trying to imagine a life built around printing: hand-set type, beautiful paper, and work that might endure. The Banyan Press had its name. What it stood for—what it could become—was still half-imagined, still taking form.

These weeks in the journal are unusually rich. Claude is surrounded by a shifting cast of friends and artists: the critic Marius Bewley; painter Robert De Niro Sr. and his wife, poet and painter Virginia Admiral; painter Marjorie Morse; translator Walter McElroy; gallerist Betty Parsons; Frances Steloff of Gotham Book Mart; French architect Pierre Chareau and his wife, Dollie; painters Alvin Ross and Alfonso Ossorio; poets and writers such as Charles Henri Ford, Gore Vidal, Djuna Barnes, and W. H. Auden; photographer Ruth Bernhard; filmmaker Maya Deren; and others. Robert Motherwell and Peggy Guggenheim appear just before and after these entries—part of the larger artistic orbit Claude inhabited. It was a world of creative unrest and aesthetic inquiry, and he was writing it all down, often the very same night it happened.

He’s also reconnecting with Anaïs Nin, who had trained him at her Gemor Press the year before (see last week’s post: Claude Fredericks & Anaïs Nin: A Diary of Love and Becoming). On April 24—Milton’s birthday—Claude visits her. They talk for hours: about love, analysis, desire, obligation, and what she calls the fatalité intérieure. She urges him to begin psychoanalysis with Clement Staff, and tells him he has a social obligation to write: that his diary—and the way he lives—together point to something deep and untapped: a kind of fountain he must learn to use.

It’s a moment of clarity. Claude returns home and bakes a cake. He quarrels with Milton, makes a beautiful meal, and later writes a poem so satisfying that he literally laughs with joy after typing it. There are flickers of doubt, creative impasse, and emotional distance—but something is starting to turn.

Anaïs would later describe him as ‘the invisible man… the felt in the bedroom slipper’. But here, in the journal, Claude is anything but invisible.

These April 1947 entries—Claude’s, never before published—capture him at a turning point. The press is taking shape. The diary is deepening. And the self, always elusive, is becoming legible.

Below is the first full page of Claude’s April 24 entry, as he typed it in 1947. The rest—along with my commentary, Anaïs’s full reflections, and more—is available to paid subscribers.

Paid Subscribers: The Full Story

By this point, the press was beginning to have a small reputation. Friends in the Village knew what Claude and Milton were doing—and what they were trying to do. So did a few writers, a few editors, and others who would become central to the Press’s future—including Carl Van Vechten, who by 1948 was giving them unpublished manuscripts of Gertrude Stein’s to print. But even as the press was becoming real, Claude was thinking about something else: leaving for the country.

These entries capture that tension—New York in full creative bloom, and the first flicker of wanting out.

This week, paid subscribers get:

The complete journal entries from April 24 and 27, 1947—Claude’s reflections on intimacy, doubt, analysis, and breakthrough.

Additional extended commentary from me, offering deeper reflections on these entries—tracing their context, artistic resonances, and the quieter tensions that give them shape.

A 2012 archival essay by Claude on the origins and ideals behind The Banyan Press.

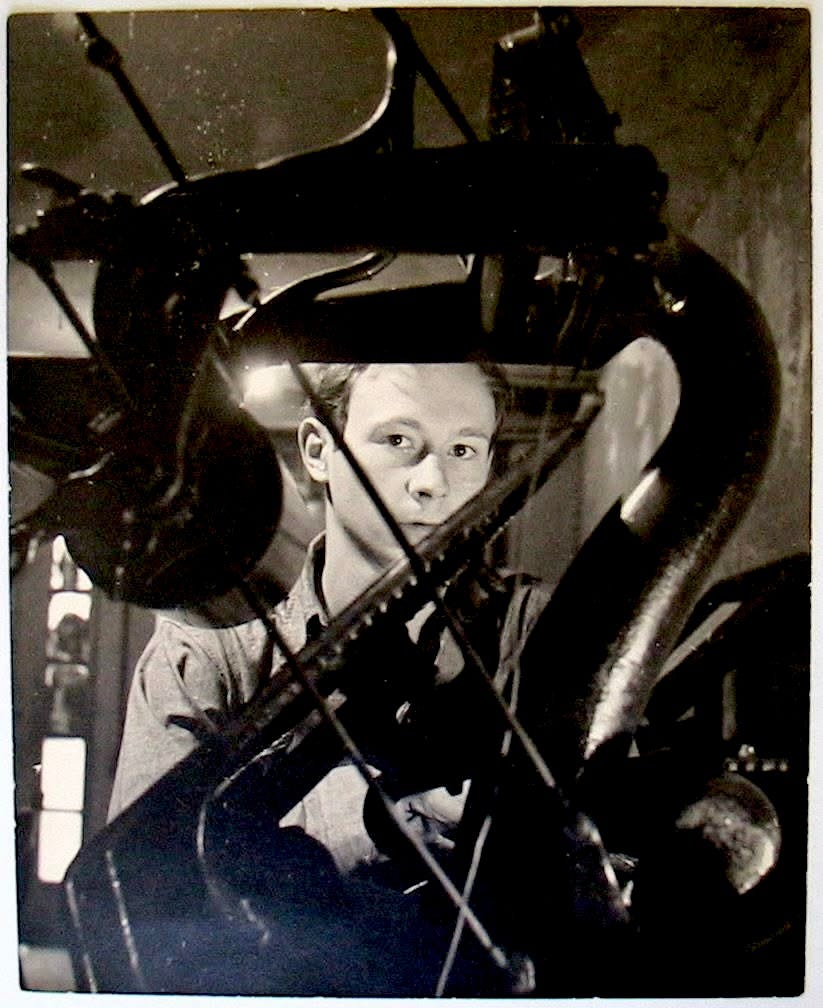

Visual archive materials, including a rare 1947 photograph of Claude and Milton in the former basement butcher shop on East 29th Street, working with Theodora, their 1906 Golding press—and a striking studio portrait of Claude taken later that same year by Carl Van Vechten in his legendary New York studio.

[🔓 Upgrade to paid to unlock full access.]

Coming Up Next

Next week, we leave the city.

In May 1947, Claude and Milton take what was meant to be a short spring trip to the country—and instead, they stumble into something lasting. They find a house in Vermont. Claude falls in love with it almost instantly, and within days, he decides to buy it. It will become his home for the next sixty-five years.

By 1950, Claude and Milton will part ways—Claude sailing to Europe, and eventually into a life with poet James Merrill. But in these entries, they are still together, still dreaming in tandem. And the house they discover in Pawlet is the beginning of a new kind of life: spacious, rural, and rooted.

It’s a kind of love story—with a place.

Stay Engaged and Share the Journey

Are you enjoying these glimpses into Claude’s world? I’d love to hear what resonates with you. Drop a comment below, or consider sharing this post with friends who might be curious about Claude, the postwar Village, or the quiet intensity of a life written down.

If you journal: What do you try to capture? Do you record what’s happened—or how it felt as it was happening?

Claude did both. And in doing so, he left behind not just a record of his life, but a way of thinking about how to live it.

—Marc

Copyright Notice: All journal entries and photographs are © Marc Harrington. No portion of these materials—whether photographs, full journal entries, excerpts, or extracts—may be used or reproduced in any form without written permission. With gratitude to the Getty Research Institute for preserving the original manuscripts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Extracts: From The Journal of Claude Fredericks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.