Reading Claude in 1964

Love, Change, and the Shape of a Life—Paris, Rome, Athens

These past few weeks for me have been full—some work, some travel, a bit of much-needed time away in Maine. I’ve been happy, honestly—Edward and I both. But as July winds down, Claude’s been especially close again. And I’ve found myself drawn to him at forty, traveling through Europe, right in the middle of things shifting.

July always brings him near. I moved here to be with him in July 1995—thirty years ago now. July 30th was our anniversary. Every year we marked it, sometimes with fanfare, sometimes just quietly at home. So this month, almost without planning it, I found myself pulled back into Claude’s journals from another July—1964—when he was traveling abroad, writing almost every day, and, in his own way, searching.

Claude Fredericks (1923–2013) kept one of the longest personal journals in history—over 65,000 pages spanning eight decades, now housed at the Getty Research Institute. A playwright, printer, teacher, and lifelong diarist, he recorded everything: daily rhythms, private longings, artistic breakthroughs, and the interior life of a man constantly in search of beauty and meaning. Through his Banyan Press, he published works by Gertrude Stein, André Gide, James Merrill, and others. In the 1950s and 60s, his own mythic, lyrical plays were staged Off-Broadway. Since January, I’ve been sharing excerpts from his journal here on Extracts—a life fully observed, and fully written. This week, we meet him in the summer of 1964: newly forty, alone in Europe, and open to what might come next.

That summer, during Bennington’s teaching break, Claude sailed to Europe—Paris, Rome, Athens—since his sabbatical wouldn’t come until 1966 (when he went to Japan—see Kyoto 1966: A Turning Point), summer was the only time he could go. So he went—because he needed to. He had turned 40 that previous October, and something in him—emotionally, spiritually, even physically—was beginning to shift.

The writing from this trip includes two letters to Bill French, a young man he’d met that spring—a recent Williams College graduate Claude had fallen for quickly, and deeply. There’s also a journal entry from Athens, and a short letter in French to a young Swiss man he’d spent a rapturous week with in Paris. As I read through them, four themes began to surface. . .

Beauty & Transience

Claude’s lifelong tension was between the city and the country. He grew up in Springfield, Missouri, but spent much of his time just outside the city, at his grandmother’s farm. His mother, Vira, had grown up there too, but she was determined to carve out something different. She’d only graduated high school, but she was a born entrepreneur. After leaving Claude Sr.—a womanizer and an alcoholic—she convinced him, and his boss, to let her take over management of the local gas station where he had been regional manager. Soon she was running several stations, then added popcorn concessions at the movie houses, then opened a thriving dress shop. She divorced Claude’s father, took over the penthouse suite at the Kentwood Arms Hotel, and by the time Claude was a teenager, she was one of the most successful women in that part of the state. That’s where he spent his adolescence: in the middle of the Midwest, living high in the sky in the finest new hotel in Springfield, Mo.

Vira always represented ‘city lights,’ as Claude liked to say. She took him to New York as a teenager for theatre, opera, concerts—Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra at Rockefeller Center. But even earlier—almost unbelievably—she took him to Europe. He was just ten or eleven, and they sailed first class on the SS Europa, then the finest of the German transatlantic liners. This must have been 1938. Claude remembered portraits of Hitler and von Hindenburg on the walls of the ship, and the pursers at dinner ceremoniousy tying swastika armbands around the children’s arms. He and Vira sat at the captain’s table. She danced with crown princes of Europe. And he remembered dancing, too—with his mother, down by the Seine on Bastille Day. There were fireworks, crowds, the shimmer of celebration. A boy on the edge of adolescence, in the last brief season before the War, caught in the dreamlike glamour of the world just before it changed.

Years later, arriving again in Paris as an adult, Claude captured something of that same dreamlike threshold—the poignancy of travel, beauty, and dislocation—in a letter to Bill French (the full text is in the paid section):

The boat-train came last night from Le Havre, disentangling all the curious relationships five days at sea engenders, awakening one with a start from the dreamed Nowhere with the noise and confusion of St.-Lazare without porters or taxis, and a thousand bewildered people trying to find their way, like sleepwalkers, back into their own lives again. Or, rather, to find their way, awakened from a dream, in a strange city. My eyes filled with tears when suddenly the taxi wheeled a corner and there before me was the Tuilleries, with its palace on the one side and on the other, far to the right, the obelisk. And that sudden breathlessness came, that comes, when body dissolves in air the way it seems to sometimes swimming in water. . .

—CF, Letter to Bill French, Paris, July 1964

Cities were never just cities to Claude. They held memory—early, sensory, emotional. They were also where he could be fully himself. New York, Paris, Rome, Athens—these were the places he imagined himself into as a gay man, a writer, a seeker of beauty and experience. He could only truly work—writing, printing—in the country; Pawlet gave him the silence and solitude he needed for that. And he could only imagine domestic love, real love, unfolding there too—like something out of Virgil or perhaps Horace, shaped by intimacy and seasons, rather than display. But he needed the cities to be reminded of what shimmered. They gave him the charge.

(And soon I’ll share more from Claude’s boyhood—he started his diary at age eight, and the Springfield years are a story all their own.)

Longing for Connection

Claude wanted not just love, but companionship—a quiet, steady life with someone who would be both partner and confidant. He wasn’t promiscuous; in fact, his gay friends, especially James Merrill and that whole New York circle, used to tease him about it. Claude had a habit of starting highbrow conversations—about art, literature, music—with men he was interested in, even in the bars. What he didn’t always realize was that many of them weren’t looking for a conversation. Often he’d lose out as a result. But that was Claude. He wanted a dear friend and a lover, someone who would share a life, not just a bed.

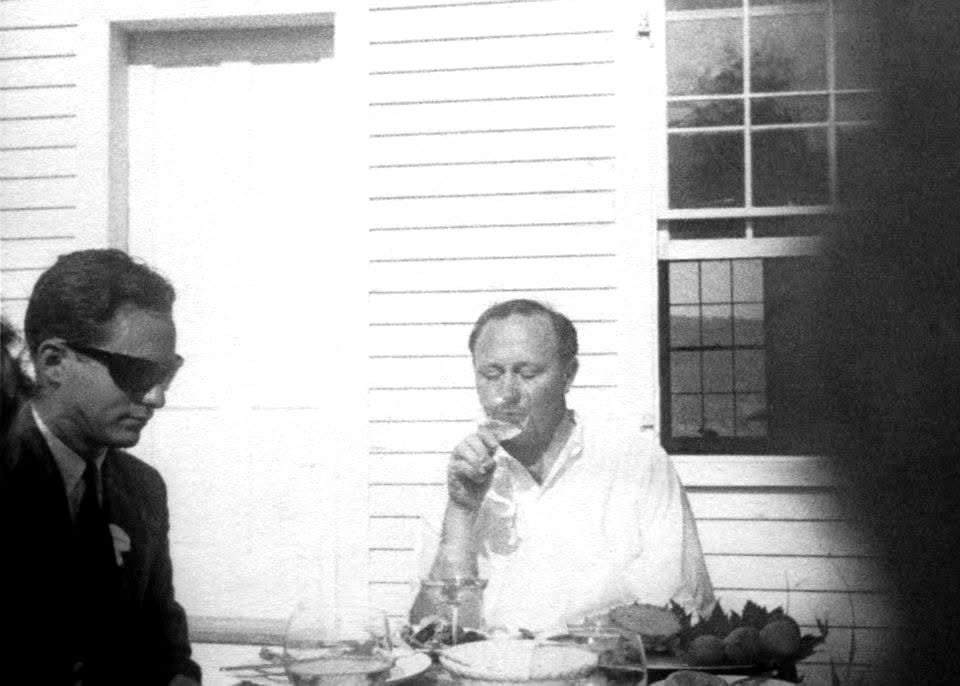

That week in Paris—on the way through Rome to Athens—Claude met a young man named Lawrence Tribollet—his name appears at the top of the letter (I wouldn’t have remembered it otherwise—where is he now, I wonder?). They’d crossed paths at the Café de Flore, in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and for a week, Lawrence stayed with him at the Hôtel des Saints Pères—recommended to Claude by his good friend and former mentor from his Harvard days, the poet John Berryman (1914-1972). Claude would recall it, even years later, as one of the most intimate and joyful weeks of his life. It had been deeply fulfilling, especially sexually—rare for Claude in those years. There was no hesitation. No game-playing. Just ease. Affection. There was real companionship between them. A week or so later, from Rome, Claude wrote Lawrence (en français)—with a kind of quiet sincerity that still moves me. I don’t know why they didn’t stay in touch, or try for something more. It seemed mutual, uncomplicated, real. From his letter (the full text is in the paid section):

Le plus beau moment que j’ai eu ici était le dernier soir, quand j’ai assisté à une représentation d’une pièce de Plaute — qui, si tu as oublié, était un auteur latin deux siècles BC — dans le Nifeo de la Villa Giulia. C’était en plein air, parmi des arbres et des fleurs, avec un lune et des statues, et les acteurs ont joué avec charme et gaieté. Aujourd’hui — un dimanche — je suis allé, le matin, au Museo delle Terme, où il y a beaucoup de sculpture grecque et romaine qui m’intéresse (surtout un beau torse grec d’un jeune athlète grecque qui m’a fait penser tout nostalgiquement de ton beau corps. . .

The loveliest moment I’ve had here was the other night, when I went to a performance of a play by Plautus—who, if you’ve forgotten, was a Latin playwright from the 2nd century BC—in the Nymphaeum of the Villa Giulia. It was in the open air, among trees and flowers, with a moon and statues, and the actors played with charm and cheerfulness. Today—a Sunday—I went in the morning to the Museo delle Terme, where there are many Greek and Roman sculptures that interest me, especially a beautiful torso of a young Greek athlete who made me think so wistfully of your beautiful body. . .

And then there was Bill French. Claude had met him in the Spring before he left for Europe through a group of young men who orbited around a bartender named Paul at the Country Restaurant in Williamstown. Paul was a little older than Bill—mid-twenties, maybe—and Bill was a recent graduate of Williams College. Claude was drawn to that world: what I’d call preppy and straight-appearing (though many weren’t). It echoed the Harvard crowd Claude had known in the early 1940s—handsome, clever, privileged boys, or at least boys just on the edge of privilege. Bill had majored in French—fitting, given his name!—and I believe he’d just begun teaching French at the Berkshire School.

Claude wanted from Bill what he would eventually find, I think, with me. A younger companion to share the days with, quietly and with affection. Looking back, I see how closely this longing mirrored the ancient Greek ideal he so revered, especially in those years—Plato’s Symposium never far from reach. It’s not lost on me that this trip to Greece followed soon after. What he wanted was someone to live alongside him in the rhythm of his life: mornings in bed with coffee and books, afternoons in the garden or at his desk, evenings with Bach or Purcell or Mozart playing through the house.

He found something like that, briefly, with Yoshihiro, whom he brought back from Japan in 1966. Yoshihiro was gay—of that Claude had no doubt—but when he returned to Japan, family expectations prevailed. He married, had a child, and slipped out of Claude’s life in a way that was quiet but final.

Later came former Bennington students David Beeken, and then Todd O’Neal. Both relationships held real feeling, and both men lived with Claude in Pawlet for years—part of the dailiness, the quiet routine he cherished. But these relationships, too, had their complications. They were young men who, in time, would identify as straight—or at least choose to live that way. And I’ve sometimes wondered, gently, whether Claude’s pull—his attention, his intellect, the way he gave himself so fully—was powerful enough to draw them not just briefly, but deeply, into his world. There was likely truth between them, even love. But not the kind Claude most longed for: enduring, mutual, and whole.

Spiritual Restlessness

Claude saw writing as a spiritual act. After he became a Buddhist in 1966, he would meditate each morning, and then, from that stillness, go straight to his journal. It became a kind of practice—focused, steady, without distraction. But even before that, long before any formal spiritual path, his writing—especially his letters and journals—was where he met himself most fully. They were sacred spaces for him, a place where he could be transparent, intimate, sometimes even more than his readers or friends were prepared for.

In Athens, where he ended his summer, he stayed in a rooming house—’Madame Sissy’s’—recommended by his friend Donald Richie, the writer and film critic, a mutual friend of James Merrill’s. Claude had originally hoped to stay at Merrill’s house (by then shared with his companion David Jackson), but Jimmy and David weren’t in Greece that summer. They’d rented it out to someone else. Still, the city felt alive to Claude—with memory, meaning, and literary spirit.

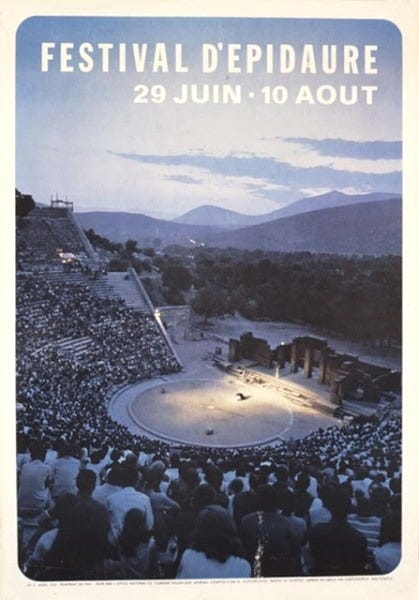

He visited the ruins—Epidaurus, Eleusis, Sounion. He read Plato. He walked through history, not as a tourist, but as someone returning to a world he’d long carried inside him. He often said his favorite writer was Plato, and his favorite work The Symposium. That tells you something about what love meant to Claude. Not just a body or a companion—but the elevation of mind and soul, the beauty of presence and understanding. Physical, yes—but also philosophical, even devotional. And of course, he taught that again and again over decades as a classics professor at Bennington—he even taught it to me, in the course Religious Experience, in 1991.

One entry from his journal that week (full text in the paid section) captures this synthesis—history, longing, intellect, devotion—almost painfully well:

And now I sit in Mme Sissy’s pension on the Odos Apollonos in Athens, having yesterday seen the unspeakable glory of the Argolid plain surrounded by its mountains, having walked through the lion gate to the top of King Agamemnon’s castle, having, the night before, seen Aeschylus in the theatre at Epidaurus, having broken into tears over and over, as I do now, at the glory of any dream made real—this is the glory of travel, as if space were time, as if all this were the heaven we do have intimations of—and most of all of this deepest and tenderest of all my dreams, Greece made a fact of my own life in a way no book does. . .

—CF, Journal, Athens, 27 July 1964

And then, just days later—still in Athens, but about to depart for Crete—his tone shifts. There’s less awe, more observation. He’s taking in the heat, the pace of the streets, the ordinary rhythms around him. He’s alone, but not lonely. Watchful. Present.

Grief & Becoming

Claude’s relationship with Hal Farmer lasted from around 1959 until early 1964. Hal was really his first true domestic partner after Milton Saul (1948–1950), with whom Claude had co-founded the Banyan Press in 1946. It was with Milton that Claude moved the press to Pawlet in 1948, when they bought the house that would become home. (You can read more about that chapter here: From New York to Vermont.) Before that was Jimmy Spicer, a friend of Julian Beck and Judith Malina of The Living Theatre—Spicer stayed mostly in New York and never gave Claude the kind of home life he wanted.

But Hal lived with Claude for those four or five years. At first, there was love there. Claude called him a ‘song and dance man’—someone with a gentle charm who loved socializing and being the life of the party. Too many martinis, though, and Hal could grow unpredictable, even volatile. Claude once found liquor bottles hidden around the house years after he’d left.

Yet Claude never spoke bitterly about him. He understood that relationship gave him something vital: proof that a life with another man, in the country, was possible.

By the spring of 1964, though, Claude was ready to move on. He didn’t walk away in anger—he simply began to shift his life. I always thought it was beautiful that at forty, he still went after those younger men. He had more to give—more to share. And that brief, rapturous week with Lawrence in Paris opened something in him.

Then there was Bill. From afar Claude began to imagine a new kind of domestic life with him. But Bill carried his own sorrows. He struggled with his identity—something that would only intensify. By late 1965, he was acting out, throwing oranges through windows at Pawlet. Eventually, he was committed at Tompkins 1 (T-1) ward at the Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital (YNHPH). Claude was devastated. He once told me he had seriously considered ending his life after Bill was taken from him—but decided, almost absently, that he ought to see Japan first. That decision would become the hinge of everything.

But none of that had happened in 1964. That summer, Claude was in motion. He had just turned forty. He was free from Hal. He was hopeful. He was going to Europe, full of expectation, and open to the possibility of finding someone to love.

This week’s paid post includes the full holograph images—the summer letters and Athens entry—offering an intimate window into Claude’s thinking at forty.

Thank you for reading Claude with me. I’d be grateful to hear what resonates with you.

—Marc

Copyright Notice: All journal entries and photographs are © Marc Harrington. No portion of these materials—whether photographs, full journal entries, excerpts, or extracts—may be used or reproduced in any form without written permission. With gratitude to the Getty Research Institute for preserving the original manuscripts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Extracts: From The Journal of Claude Fredericks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.