From New York to Vermont

Claude Fredericks, The Banyan Press, and the Search for a Life Beyond the City

The final post in a three-part series tracing Claude’s early years as a printer and the founding of The Banyan Press — a journey that began in New York City in the mid-1940s and, by the spring of 1947, turned north toward Vermont, and toward a quieter life still taking shape.

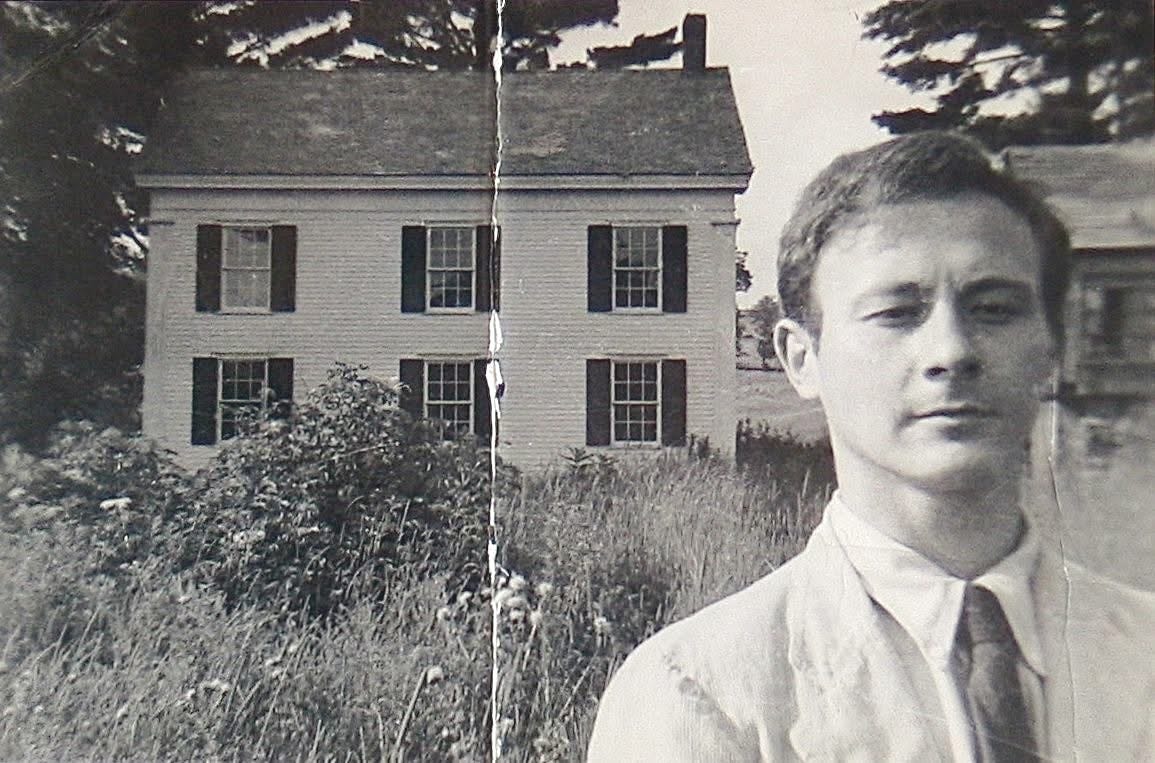

Claude Fredericks (1923–2013) kept one of the longest personal journals ever written—more than 65,000 pages across eight decades, now housed at the Getty Research Institute. A printer, playwright, teacher, and diarist, Claude recorded everything: daily rhythms, private longings, and moments of profound artistic insight. Through his Banyan Press, he published works by Gertrude Stein, André Gide, James Merrill, and many others. Since January, I’ve been sharing excerpts from his journal here on Extracts—inviting readers into a life fully observed, and fully written.

A Mark That Endures

If you’ve been following Extracts for a while, you’ve seen it — that small, stark emblem at the top of every post: a white tree, cut into a square of color.

It doesn’t quite resemble a banyan. In fact, Claude first saw the shape carved into the doorframe of an old farmhouse near here, in West Pawlet, in 1947 — a bit of folk ornament, worn and stylized, almost like a fat corn stalk or flowering plant. I still look for it every time I drive by that house. It’s still there.

Claude redrew it, cut it as a linoleum block, and adopted it that year as the colophon for The Banyan Press — not because it looked like a banyan tree, but because it felt like what he wanted the press to stand for: something grounded, organic, enduring.

Sometimes it appeared at the back of his books. Sometimes at the front. But always it was there — a quiet signature, a symbol of care, integrity, and lasting work.

I’ve adopted it here on Extracts for the same reasons: to mark this project, to honor that lineage, and to carry forward a way of making that Claude believed in deeply — one book, one page, one entry at a time.

Leaving the City

By early May 1947, Claude and his partner, Milton Saul, were feeling the edges of their New York life.

The press had begun. Books were circulating. Writers and editors were taking notice — Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams, Carl Van Vechten, and Judith Bailey, a poised young editor Claude knew socially, who appears in this week’s pages. She would later become Judith Jones — the Knopf legend who brought The Diary of Anne Frank to American readers and introduced the world to Julia Child.

The authors they were publishing — William Jay Smith, Stephen Spender, even Tristan Corbière (in translation) — already had readers, but the Banyan editions were being noticed. Reviews appeared in The Sewanee Review, Voices, and The New York Times.

By 1948, Time magazine had taken note as well, describing their edition of Gertrude Stein’s never-before-published Blood on the Dining Room Floor as ‘an example of the bookmaker’s art… a delight to hand and eye.’

But postwar New York carried its own tensions — not just the noise and crush of city life, but the deeper unease that settled over the country in those early Cold War years. The atomic bomb was no longer theory; it was real, and its shadow fell across daily life. There were jitters, rumors, the steady thrum of geopolitical strain. For many, including Claude, it stirred a longing for someplace quieter, more rooted — a place beyond reach, where a different kind of life might be possible.

Their friend, the painter Robert Motherwell — who had recently built himself a Quonset hut studio on Long Island — had planted the seed: leave the city, find land, build something of your own.

At first, Claude imagined a studio — a structure for the press, something functional and spare. But as they talked and planned, their vision shifted. They began to picture a home. A place to work, to live, to grow into.

The Search for a Life

Claude’s entries from May 3, 1947 — morning and noontime — look back on a journey just completed. The tone is clear-eyed, still humming with memory.

They had left New York on Sunday, April 27 — driving first to Rye, the town Milton had grown up in, where they stopped to visit his parents. Then they wound their way through Kingston, Phoenicia, Walton, and Deposit, before crossing into Pennsylvania and spending the night in Forest City. The next morning, they pushed on through Hazelton and East Stroudsburg. Another night in Great Barrington. Then north again through Eagle Bridge.

By April 30, they had reached Bennington, Vermont — and checked into the old Putnam Hotel.

It was Claude’s first time in the state.

The next morning — May 1 — they met a realtor in Manchester, and drove north together into the Mettawee Valley: past Dorset, into Rupert, with the Taconic range to the west and the Green Mountains rising to the east.

Somewhere along that stretch, the realtor pointed out a house in the distance — a good mile off the main road, nestled into the lower slope of the Green Mountains, just inside the Pawlet town line. It had been sitting on the market for some time, priced a little high at $9,000. But it was available — and something about it caught Claude’s attention.

He didn’t hesitate.

For me it was a 'coup de foudre' the very moment we arrived. A handsome house. Inside it proved even more handsome—14 marvelous rooms, large and simple, an excellent shed adjoining the house for the press. Greek Revival, built around 1830, excellent slate roof, perfect slate foundation, excellent beaming, and a beautiful view of valley or mountain from every one of its twenty-seven windows. A big studio on the second floor, a spacious attic. And outside a beautiful stream with many small cascades, the gorgeous mountain above, big old pines, four of them, in the yard—everything ideal. I fell in love with it completely. . .

—Claude Fredericks, 3 May 1947

They made arrangements at once to buy the place — the house and all 150 acres that came with it — with help from Milton’s GI Bill and Claude’s mother, Vira.

The beauty of the house was unmistakable. But what lingered was the steadiness it promised — a place to work, to live, to belong for more than just a season.

Milton and the Life to Come

Milton Saul — Claude’s partner at the time — came from a very different world.

The son of a well-off suburban family, he had gone to Princeton, then served in the Navy during World War II. Claude once told me how Milton survived the torpedoing of his ship in the Pacific — clinging to wreckage until rescue arrived. It was a defining experience, though one he rarely spoke of.

Their life together in New York had been intense and creative — but it was also provisional. They were young. They were printing books by hand in a basement butcher shop on East 29th Street. They were baking bread, writing poems, figuring out what their life could be.

Anaïs Nin, Claude’s mentor and friend, was wary of Milton — finding him too conventional, too domestic for the artistic world they inhabited. But others, like Carl Van Vechten, loved them as a pair. He affectionately called them The Banyan Tots — young and earnest and already making something that mattered.

The house in Pawlet gave their life a new shape. A future. They bought it together in 1947, and by the spring of 1948, they had moved in — setting up the press, planting a garden, and learning the rhythms of rural life.

But by 1950, the relationship had quietly come undone. Claude fell in love with the poet James Merrill and left for Europe to be with him. He wouldn’t return to the house in Pawlet until late 1952.

Still, something had taken hold there — something that would last.

And when he did come back, he returned for good.

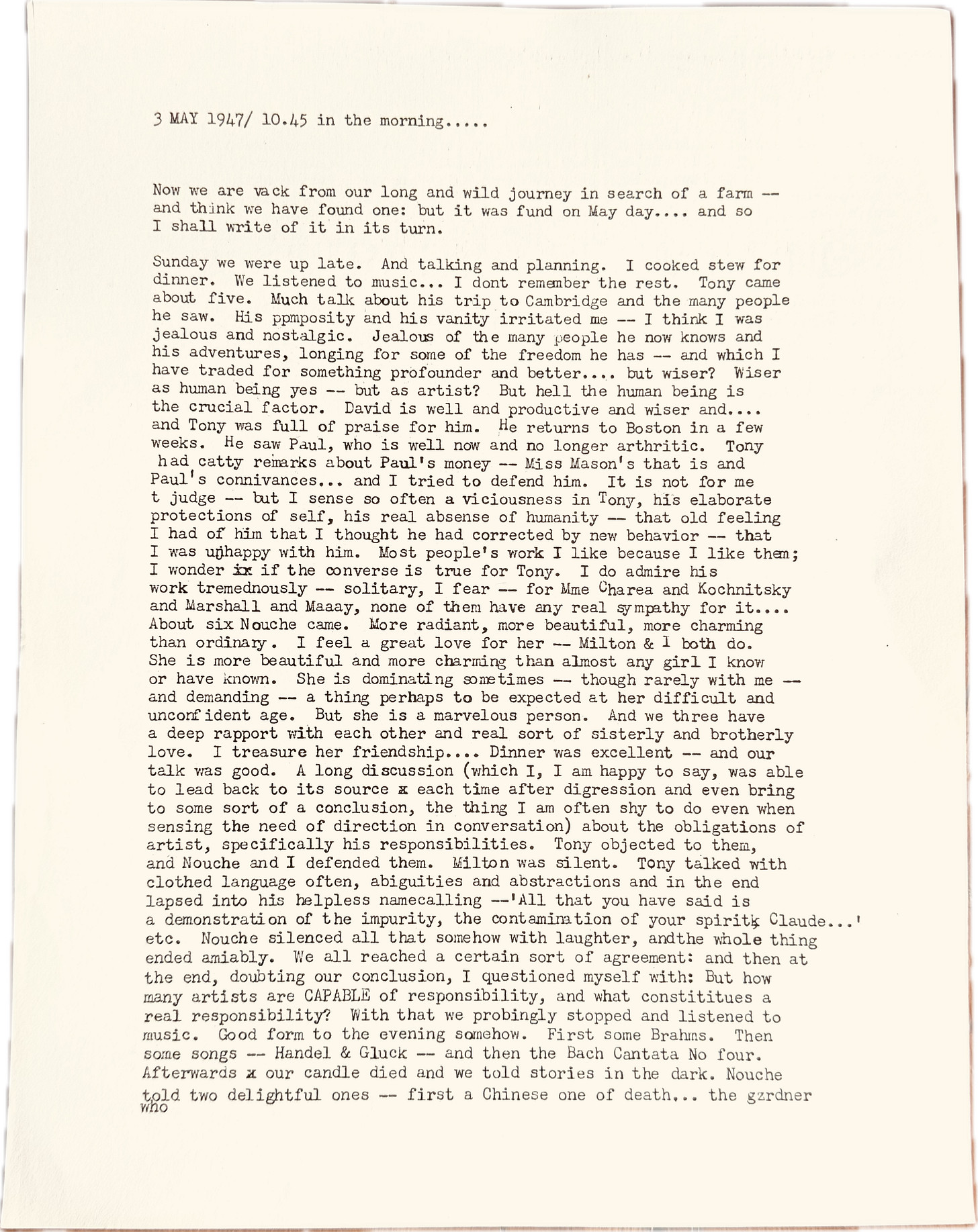

A Glimpse Into the Pages

Below is the first page of Claude’s May 3, 1947, journal entry — written that morning, just after returning from what he calls ‘our long and wild journey in search of a farm.’

They had found it — the house in Pawlet. But Claude holds off describing it right away. ‘It was found on May Day,’ he writes, ‘and so I shall write of it in its turn.’

Instead, he begins by recounting the quiet Sunday just before they left — a day spent in their cold-water flat off Third Avenue. He cooks a stew. They listen to music. And that evening, they host a small gathering of friends, full of conversation about art, obligation, solitude, and the strange labor of becoming oneself.

It’s a portrait of domestic life on the cusp of change — intimate, questioning, still grounded in the city but already tilting north.

The full entry — and what follows later that night, after he’s seen the house — is available for paid subscribers.

For Paid Subscribers: This Week’s Archive

This week, I’m sharing an especially rich trove of archival material — a way of bringing you deeper into the world Claude was beginning to shape.

Included for paid subscribers:

The full journal entries from May 3, 1947 — tracing Claude’s journey north, his reflections before they set out, and the moment he first saw the house that would become his for the next sixty-five years.

A 106-image photo album of Banyan Press materials — books, broadsides, ephemera — photographed by me in the archives of the Getty Research Institute.

A complete bibliographical checklist of The Banyan Press, compiled by J.M. Edelstein. Originally published in American Book Collector, Volume 7, Number 3 (March 1986).

A First List of Books Printed and Published by The Banyan Press (1948) — A high-resolution PDF with Carl Van Vechten’s luminous and wry foreword.

[🔓 Upgrade to paid to access these rare materials.]

Next Week in Extracts

Claude had been writing plays since boyhood — especially radio plays, which he loved for their intimacy and immediacy. But by the early 1950s, with the press now rooted in Vermont, he turned to drama with new focus and ambition.

He began crafting works for the stage — mythic, lyrical, searching — and before long, his plays were being performed in New York: first by the Living Theatre, and later Off-Broadway at the Artists Theatre. The Idiot King, On Circe’s Island, A Summer Ghost — each one its own act of lyrical risk and quiet reckoning.

For Claude, the theater became another kind of press — a space for voice, presence, and transformation.

We’ll open this next chapter soon — with rare photos, full journal pages, and a glimpse inside the plays themselves.

Until then,

—Marc

Copyright Notice: All journal entries and photographs are © Marc Harrington. No portion of these materials—whether photographs, full journal entries, excerpts, or extracts—may be used or reproduced in any form without written permission. With gratitude to the Getty Research Institute for preserving the original manuscripts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Extracts: From The Journal of Claude Fredericks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.