Claude Fredericks & Anaïs Nin: A Diary of Love and Becoming

Claude's 1946 diary captures his brief but profound entanglement with Anaïs Nin—and a world of postwar artists, longing, and creative awakening. . .

This is the first in a three-part series exploring Claude Fredericks’s life in New York City during 1946–1947—a moment of artistic immersion, emotional upheaval, and creative becoming. These entries trace his friendships with Anaïs Nin, Gonzalo More, and a constellation of artists, musicians, and poets who filled the postwar Village. They also mark the beginning of something enduring: the founding of the Banyan Press, which Claude would bring with him to rural Vermont in 1948.

Claude Fredericks (1923–2013) kept one of the longest personal journals ever written—over 65,000 pages across eight decades, now housed at the Getty Research Institute. He wrote daily, with precision and depth, recording the texture of ordinary life alongside moments of profound transformation. A printer, playwright, teacher, and diarist, Claude published works by Gertrude Stein, André Gide, James Merrill, and many others through his Banyan Press. Since January, I’ve been sharing excerpts from his journal here in Extracts.

Greenwich Village, 1946

In the summer of 1946, Claude Fredericks found himself in Greenwich Village, nearly 23, working at a chaotic little press run by Anaïs Nin (1903–1977) and her mercurial former lover Gonzalo More (1892–1950), a Peruvian Marxist. Claude wasn’t there long—perhaps just a month or two—but the impressions left behind were indelible. As were the pages.

The diary entries you’re about to encounter (spanning June 12–19) have never before been published, excerpted, or made public. They represent the most complete, psychologically intimate, and emotionally unguarded account we have of Claude’s brief time in Anaïs’s world—and of the many entanglements and revelations that surrounded it.

By 1946, Anaïs Nin was already herself: erotically mythologized, intellectually ravenous, a writer who seemed to consume the lives of those around her almost as avidly as she chronicled her own. The Gemor Press—the venture she had launched a few years earlier to self-publish her writing (and give Gonzalo something to do)—had become a charged little space of bohemian ambition and romantic upheaval. Claude stepped into this fevered scene—and, crucially, began writing about it.

The press was a place of making, yes—but also of close creative entanglement. Frances Steloff, the legendary bookseller at Gotham Book Mart, helped distribute the limited editions Anaïs printed there. A few years later, she would turn to Claude and his Banyan Press for the same kind of work—fine, hand-set editions that carried a different kind of seriousness. Their paths were already curving toward each other, even then.

This was also the moment just after Richard Brewer (1923–2014)—a young painter Claude had briefly loved—left the city. Brewer would go on to become a deeply gifted, largely unsung figure in postwar American art: known for his male nudes, his intimacy with the second-generation New York School, and a circle that included Nell Blaine, Leland Bell, and Louisa Matthiasdottir. But here, in June 1946, he is simply ‘Richard’—an absence, a wound. These entries pulse with the ache and aftermath of that abandonment. And so what unfolds is not merely a glimpse into literary New York in its postwar ferment, but something harder to categorize: a soul cracking open, reaching toward love, art, and some kind of personal clarity. And then—just days later—this moment with Anaïs.

A Shared Language

I had lunch with Anaïs, taking my novel for her to read. A profound and serious conversation, in which I spoke in detail of much of my life, and she of hers, and we understood each other and had a rapport we never had had before. We couldn’t talk fast enough. We found ourselves amazingly similar. Both of us have been motivated our whole lives in seeking love, and our conception of it is similar.

—Claude Fredericks, 16 June 1946

He writes of his mistrust of kindness, his shyness around sex, the strange seductions of power, the texture of New York streets, the loneliness that trailed even the most exquisite connections. And above all, he writes of Anaïs. Their conversations about journals, about domination and freedom, about homosexuality and tenderness—these passages are electric. They read like two diarists meeting inside the mirror, comparing reflections, quietly measuring the damage and the glory of self-revelation.

For Claude, it’s a moment of becoming. He’s not yet the publisher of Gertrude Stein (though by 1950 he would be), or of John Berryman, James Merrill, Richard Eberhart, or André Gide. Not yet the printer of Thomas Merton, Charles Simic, or Robert Duncan. Not yet the teacher, or the friend I knew. He’s just beginning. But the voice is already his.

Here are a few glimpses from the entries:

We spoke of an ideal love—of proper, mature love between two people: where there is an equal giving and taking. . .

I think I could fall passionately in love with her. Even this way I fancied myself at unguarded moments strangely infatuated with her. . .

Until I can break the pattern, I shall be sick. . .

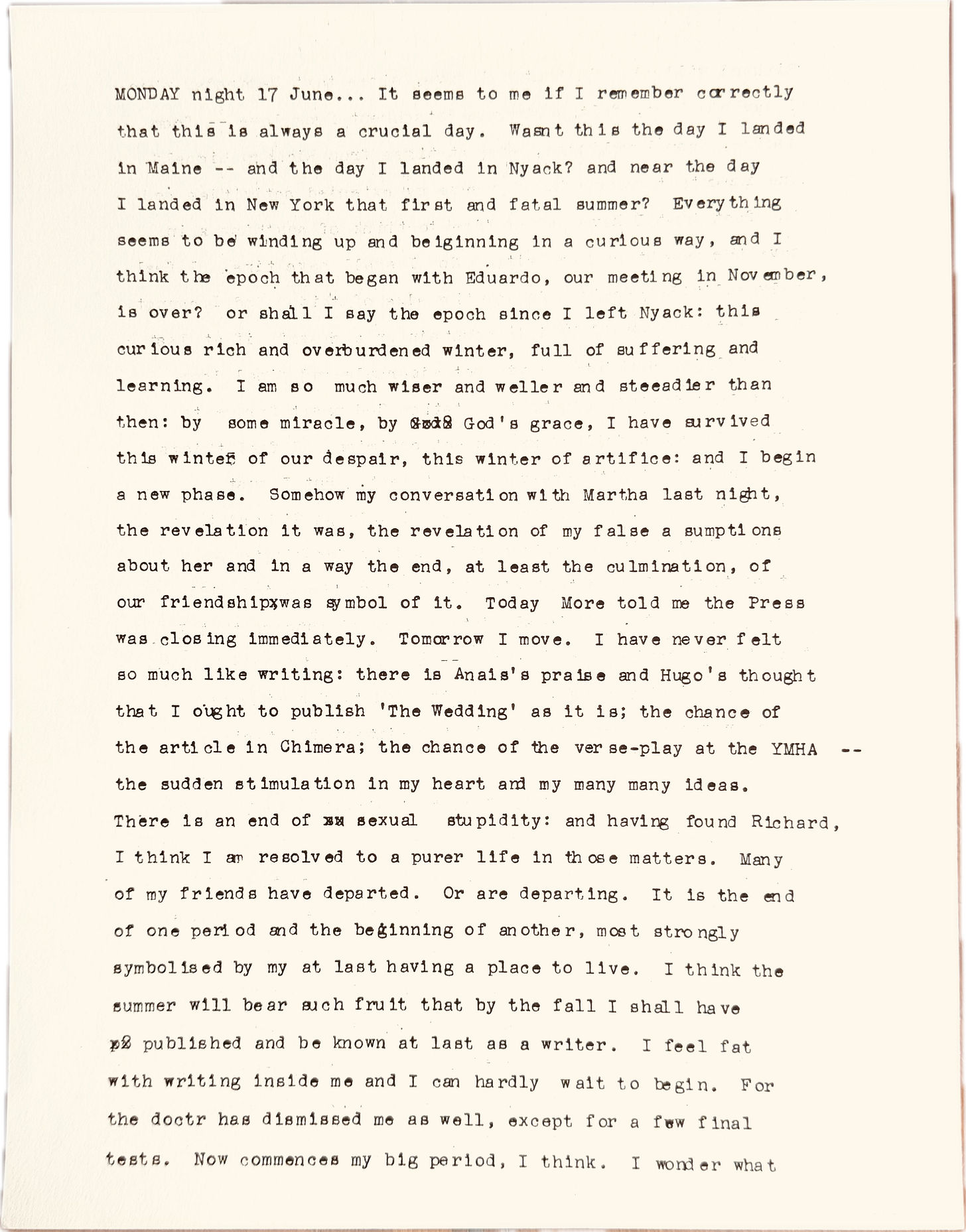

This is the first page of Claude’s June 17, 1946 entry—a turning point in mood and meaning. His ‘big period’ begins here, with clarity, ache, and a flicker of new resolve:

To read the full entries—including all 49 pages spanning June 12, 16, 17, and 19—please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Claude’s journal captures a vivid web of personalities: the young painter Robert De Niro Sr., his wife Virginia Admiral, and their infant son (future actor Robert Jr.); the filmmaker Maya Deren; and many others moving through New York’s postwar cultural underground.

You’ll also gain access to my extended commentary, where I unpack these pages further—adding context, connections, and reflections drawn from across Claude’s vast archive—along with high-resolution scans of every manuscript page.

Looking Ahead

In next week’s edition, we’ll stay with Anaïs—but widen the lens to include the art world of 1940s New York that surrounded her. This is the world Claude captured with remarkable intimacy and detail—the very reason the Getty Research Institute sought to acquire his journals. It wasn’t the literary names alone that drew them in. If anything, those were incidental. What mattered more was the atmosphere he recorded: the postwar swirl of artists, dancers, printers, filmmakers, and seekers trying to reassemble meaning. Claude was inside that world—and he wrote it down.

As part of next week’s installment, I’ll also share images of several books Anaïs inscribed to Claude—titles like This Hunger (1945) and A Spy in the House of Love (1954). These inscriptions are traces of a literary friendship that unfolded across decades, and across pages.

Paid Subscribers get access to:

Claude’s full journal entries from June 12, 16, 17, and 19, 1946

High-resolution images of all holograph pages

Additional archival photographs and ephemera

[🔓 Upgrade to paid to unlock full access.]

Copyright Notice: All journal entries and photographs are © Marc Harrington. No portion of these materials—whether photographs, full journal entries, excerpts, or extracts—may be used or reproduced in any form without written permission. With gratitude to the Getty Research Institute for preserving the original manuscripts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Extracts: From The Journal of Claude Fredericks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.